Snakes explained: Correcting misinformation about Australian snakes

By Ross McGibbon

About the Author

The information I provide on this page derives from a life-long obsession with snakes, coupled with my experience working with these animals professionally, both as a snake catcher and a wildlife photographer specialising in venomous snakes. I use the content I capture in the field to be an ambassador for reptiles and educate the public about snake safety and awareness via my online platforms (YouTube, Facebook, Instagram & Flickr).

In my spare time, I study reptiles (unofficially) and strive to keep up to date on new research and anything reptile related. The topic of venom and snakebite are of particular interest to me. Furthermore, I am a full-time career firefighter, and I'm passionate about public safety. As a firefighter, I am qualified in advanced First Aid, and I have first-hand experience in snakebite treatment (both as the patient and the one providing the First Aid). I believe at this stage in my life, I have the required knowledge and experience to advise the public on snake safety and awareness.

Image - Photographing A beautiful Black Tiger Snake in the Tasmanian highlands, Australia

_________________________________________________________________

SHORT FILM: DEADLY AUSTRALIAN SNAKES & THEIR BEHAVIOUR

DON’T MISS my educational film, where I cover everything Australian's should know about venomous snakes and their behavior. In this short film, you’ll witness fascinating, never-before-seen footage of Australian venomous snakes. I’ll share vital information about these snakes and reveal the truth behind snakebites and animal-related fatalities in Australia. You’ll also get a detailed breakdown of the defensive behaviors of Australian venomous snakes, and I’ll demonstrate the proper way to respond if you encounter one.

_________________________________________________________________

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Australian snakes the deadliest in the world?

When are Australian snakes most active?

Do Australian snakes hibernate or brumate during Winter?

Are snakes more aggressive during mating season?

What is a dry bite and why does this occur?

What to do if a snake reacts defensively to you?

What should do if I encounter a snake?

Are Australian snakes territorial?

Do snakes protect their young or eggs?

If I see a baby snake, will there be a protective parent around?

Can you identify a non-venomous from its larger head size?

Is a King Brown Snake a Black Snake or a Brown Snake?

Am I protecting my family by killing snakes?

What action can I take to prevent snakes and keep my family and pets safe?

Australian Snakebite first Aid

_________________________________________________________________

Are Australian snakes the deadliest in the world?

Australia is home to over 215 species of snakes—more than any other country. Nearly half of these are terrestrial (land-dwelling) venomous snakes. While this might sound daunting if you dislike snakes, only about 40 of these terrestrial species possess venom considered potentially life-threatening to humans. Of these 40 species, roughly 10 have been recorded as responsible for human fatalities.

Many of Australia's highly venomous snakes gained infamy in 1979 when they topped the charts in the LD50 test for having the most potent venom in the world. Several well-known Australian venomous snakes were tested, along with a selection from overseas, which resulted in a list of "the most venomous snakes in the world." However, since these results were published, they have been widely misinterpreted. The media, the public, and snake enthusiasts alike have put their spin on it to suit their agendas, often wearing the information like a badge of honor at the expense of the snake's reputation.

How many times have you heard that Australia has 9 of the top 10 deadliest snakes in the world, or that a snake enthusiast boasts, "This snake is the second most venomous in the world?" If you do some research, you’ll find that the LD50 test was purely an academic exercise designed to compare venom toxicity across a sample of snake species using standardized test subjects—mice. The results were not meant to measure how dangerous or deadly these snakes are to humans.

Below are some major shortcomings of using the 1979 LD50 test results as the basis for ranking snakes as the "most venomous," "deadliest," or "dangerous" in the world:

- The LD50 test used mice as test subjects, not humans. The results don't accurately represent how harmful the venom is to humans.

- The test only used mice. Since venom evolves to be most effective on a snake's preferred prey, the results would likely differ if the venoms had been tested on frogs, birds, lizards, or other prey types. It is no coincidence that rodents are the preferred prey of most of the top-ranking snakes on the LD50 list.

- The test didn’t include all of the world’s 600+ venomous snakes. Many species were left out, and numerous new species have been discovered since 1979. Moreover, there have been significant taxonomy changes (classification/naming of species) since then.

- The LD50 test doesn’t account for venom yield. For example, the eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis) is around two and a half times more toxic than the coastal taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus). However, the coastal taipan can inject 20 to 30 times more venom. As a result, the real-life impact of a taipan envenoming could be much more severe than that of an eastern brown snake.

To summarise, the LD50 test is a valuable scientific tool for comparing venom toxicity, given that human testing is unlikely. However, the results should not be used to determine how dangerous or deadly a species is to humans. Furthermore, the terms "dangerous," "deadly," and "most venomous" are not synonymous.

To assess how dangerous a snake species might be, several critical factors must be considered, including the snake's size, behavior, temperament, habits, venom yield, fang size, prey type, rates of envenomation in humans, number of fatalities attributed to the species, the likelihood of human contact, and how the venom affects humans.

The term "deadly" refers to how many human fatalities are attributed to a species (usually reported annually). Snakebites cause between 81,000 and 138,000 deaths worldwide each year, but Australia accounts for only about two fatalities annually. Our snakes are certainly not the deadliest.

In conclusion, Australia does indeed have more venomous snakes than any other country and the highest number of medically significant snakes (those with venom that can be life-threatening to humans). However, for their venom to become life-threatening, a bite and successful envenoming must occur. Our snakes don’t bite or envenom many people. Australia records around 200 to 500 snakebite cases annually, with about 100 requiring antivenom. On average, only two human fatalities occur each year. In contrast, India records around 50,000 snakebite deaths each year. So, are Australian snakes the deadliest or most dangerous in the world? Not by a long shot.

As a member of the public, avoid relying on questionable sources of information about snakes, such as mainstream media (newspapers, TV) or social media. Stick to factual information from reputable sources like recently published reptile books and literature or local reptile professionals. Focus on practical information—know which potentially dangerous snakes live in your area, learn the precautions to minimise the risk of being bitten, and understand what actions to take if you suspect you've been bitten.

_________________________________________________________________

When are Australian snakes most active?

All aspects of a snake's life depend on its ability to regulate body temperature, whether it's hunting prey, digesting a meal, finding a mate, fighting off disease and infection, or even pumping blood around its body. Since reptiles cannot generate their own internal body heat, their activity levels are influenced by the climate. As a result, snake activity patterns can vary significantly with the seasons. For most Australian reptiles, activity increases during the warmer months and decreases in the cooler months.

When spring arrives in September and the weather begins to warm up, activity levels increase dramatically. The warmer temperatures trigger most Australian snakes to breed. Female snakes need to hunt more to prepare for the development of their eggs or young during mating season, while males travel long distances in search of reproductive females. In some species, males compete for mating rights by engaging in male-to-male combat.

All this activity requires considerable energy and a lot of food, which is why snakes are far more active in spring and summer. During this period, it's important to be prepared for potential snake encounters and take appropriate precautions around the home.

Image above: Lowlands Copperheads (Austrelaps superbus) emerging from the vegetation to bask in the sun, Bakers Beach, Tasmania

Image above: Lowlands Copperheads (Austrelaps superbus) emerging from the vegetation to bask in the sun, Bakers Beach, Tasmania

_________________________________________________________________

Do Australian snakes hibernate or brumate during Winter?

To answer this question, it's important to first provide a brief overview of the term brumation. This term was coined in 1965 by Wilber W. Mayhew, who wanted to distinguish that 'cold-blooded' reptiles (ectotherms) do not undergo the same physiological processes as other animals, such as birds and mammals (heterotherms or endotherms), do when they hibernate. The term gained popularity among reptile enthusiasts and remains the preferred term today. Despite its widespread use, there are some objections to the term’s validity, as well as debates over whether a separate term for ectotherms is necessary at all.

The term hibernate itself doesn’t refer to any specific physiological changes or metabolic processes. It simply means to spend winter in a dormant or inactive state. Essentially, brumation means the same thing.

If you'd like to explore this topic further, you can visit this link - https://theobligatescientist.blogspot.com/2010/11/do-reptiles-hibernate-or-brumate.html#more

My advice is to use the term brumation when referring to dormancy in reptiles, and hibernation for mammals, to avoid lengthy debates with reptile enthusiasts.

So, do Australian snakes hibernate/brumate during winter?

Yes, most species in cooler climates become dormant or inactive to varying degrees during winter; however, the duration of this period depends on the species and the climate. Keep in mind that Australia is a vast continent, and the climate in northern Australia can differ greatly from that of the southern regions during winter.

In northern tropical parts of Australia, where temperatures are extreme in summer, some snakes, such as the Coastal Taipan, prefer to breed during winter. Male taipans become more active in winter as they search for females. On the other hand, snakes living in cooler climates, such as tiger snakes and copperheads, are very cold-tolerant and may remain active during winter if temperatures allow. Therefore, in some parts of Australia, it’s a mistake to think that you won’t encounter snakes during winter.

Image above: Coastal Taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) Mount Molloy, North Queensland

Image above: Coastal Taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) Mount Molloy, North Queensland

_________________________________________________________________

Are snakes more aggressive during mating season?

During the mating season, some species of snakes engage in male-to-male combat to compete for the opportunity to mate with a nearby female. The males "wrestle" each other—often mistaken for mating behaviour—in an effort to determine which one is superior. After the contest, the weaker male retreats, while the victor earns the right to mate with the female.

While this behaviour is somewhat aggressive towards their rival, there is no scientific evidence to suggest that male snakes become more aggressive towards humans during this period. However, some people still believe snakes are more aggressive during the mating season, and I offer the following explanation for this belief.

After a period of dormancy or inactivity during the cooler months of the year (brumation), snake activity increases dramatically, peaking in spring and summer. Warmer weather triggers snakes to become active as they search for food and mates. Males are more commonly encountered at this time, usually with one goal in mind—finding females. The mating season prompts male snakes to track females using scent trails left behind. When a male snake unknowingly follows a scent trail into residential areas, the likelihood of encounters with humans and pets increases.

When a snake unexpectedly encounters a person or pet at close range, it may react defensively. This behaviour is not an indication that snakes are "more aggressive during the mating season." Rather, they are simply coming into contact with humans and domestic animals more frequently during this time and will defend themselves, just as they would at any other time of year. In summary, the increased frequency of encounters during the mating season leads to more conflicts with snakes, not an increase in aggression levels among male snakes.

Image above: Highlands Copperhead (Austrelaps ramsayi) Barrington Tops NP, New South Wales (Photographed while gravid - active in breeding season). Highlands Copperheads are such beautiful natured snakes. They generally avoid biting unless stood on or severely harassed.

Image above: Highlands Copperhead (Austrelaps ramsayi) Barrington Tops NP, New South Wales (Photographed while gravid - active in breeding season). Highlands Copperheads are such beautiful natured snakes. They generally avoid biting unless stood on or severely harassed.

_________________________________________________________________

In general, snakes are not aggressive animals. Most species of snakes are shy, reclusive creatures that prefer to avoid conflict whenever possible. They do not actively seek out confrontation with humans or other animals. Instead, snakes are usually defensive, responding to perceived threats with behaviours designed to protect themselves. These behaviours, such as hissing, striking, or posturing, are usually a last resort and are meant to discourage any potential threat from coming closer. Read on to learn about defensive behaviour in detail.

_________________________________________________________________

When a snake suddenly encounters a larger animal, such as a human or a pet, it generally feels threatened by its size and may respond in one of the following three ways: Fight, Flight, or Crypsis.

Crypsis

Crypsis comes from the Greek word meaning "hiding" or "concealment." It refers to an animal's ability to blend into its surroundings, often to avoid detection by predators. For a snake, achieving crypsis means remaining completely still and using its colour, pattern, and shape to camouflage with the environment. In the presence of a predator or perceived threat, a snake will often rely on this ability to avoid being seen.

Flight

Flight, or fleeing, occurs when a snake retreats to the nearest available cover upon being disturbed. This is the most common response for wild animals, especially snakes, as it reduces the risk of injury or death from confrontation.

Sometimes, fleeing is as simple as disappearing into nearby vegetation or seeking shelter in a hole. However, if a snake is confronted while crossing open ground—such as a front lawn—the nearest cover or escape route can sometimes be behind the person. When the snake tries to flee for cover, it may appear as if it’s heading straight for us or "chasing" us. In reality, the snake is simply trying to reach safety and is attempting to get past the person in its path.

Fight

Fight occurs when a snake feels it must stand its ground and act offensively to ward off a perceived threat. In these situations, a snake may display the following behaviours:

- Rearing Up

- Flattening of the Neck

- Mouth Gaping

- Thrashing

- Mock Strikes, Lunging, or Head Butts

- Offensive Advances (Charging)

- Biting or Dry Biting

These behaviours are anti-predator strategies, also known as defensive behaviours. They are designed to make the snake appear more threatening, thereby deterring the predator. However, these actions are often misunderstood, and it’s important to recognise them as defensive rather than aggressive.

Rearing

In the animal kingdom, smaller animals typically back down when faced with larger opponents. Snakes, being close to the ground and relatively small in stature, need to appear larger in order to ward off potential threats. To achieve this, snakes will rear up their forebodies off the ground, making themselves appear taller and more intimidating.

Above image: Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) performing rearing, Rocky Gully, Western Australia

Above image: Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) performing rearing, Rocky Gully, Western Australia

Flattening of the Neck

By flattening its neck, a snake can appear larger and more intimidating than it actually is. This behaviour is most famously associated with cobras, which expand the skin around their necks to form a hood. However, some Australian snakes—such as tiger snakes, red-bellied black snakes, and mulga snakes—also perform this behaviour effectively.

Neck flattening can occur in two ways:

-

Vertical Display (Rearing): When a snake rears up and flattens its neck, it aims to look taller and more threatening to a potential predator.

-

Horizontal Display (Side-Angle): In this defensive posture, the snake flattens its neck and holds it horizontal to the ground. This side-angle display further adds to the snake's apparent size, helping it to appear more dangerous.

This neck flattening behaviour can be used in combination with rearing or as a standalone defensive posture, depending on the situation and the perceived threat.

Mouth Gaping

Mouth gaping is a defensive behaviour that communicates agitation or stress in snakes. This behaviour can range from subtle to dramatic, depending on the level of threat the snake perceives.

-

Subtle Mouth Gaping: A snake may drop its lower jaw slightly, signalling that it’s feeling agitated or threatened. This can serve as a warning to a potential predator or threat.

-

Full-Mouth Gape: If the snake feels the need to maximise intimidation, it will open its mouth wide, revealing its fangs and the inside of its mouth. This dramatic display is meant to scare off the threat by showing the snake’s potential for defence.

Both Taipans and Brown snakes are well-known for this behaviour, using mouth gaping as an effective means of deterrence when they feel threatened or cornered.

Thrashing is a defensive behaviour used by snakes to confuse predators and make it harder for them to seize a fast-moving target. By rapidly moving their bodies in an erratic manner, snakes can disorient the predator. Additionally, thrashing can kick up leaf litter, dust, or debris, further obscuring the predator’s view and increasing the snake’s chances of escape.

Mock Strikes, Lunges, and Head Butts

Mock strikes and lunges are defensive behaviours where the snake feigns a strike, similar to a boxer throwing a feint. These actions are designed to give the impression of an attack without the risk of injury to the snake. The purpose is to intimidate or put the opponent on the back foot while avoiding physical contact.

Snakes may also use head-butts to avoid damaging their fangs. Biting something unnecessarily could harm the fangs, potentially preventing the snake from feeding until they regenerate.

Offensive advancing

When people report being "chased" by a snake, they often misunderstand the snake's behaviour. In reality, snakes do not chase humans with the intent to bite or inject venom. What they are actually doing is offensive advancing—charging towards a perceived threat to force it to retreat. This is a defensive behaviour designed to intimidate and warn off potential predators, not to attack.

Similar to how an elephant might charge an intruder and then return to its herd when the threat backs off, a snake may charge if you get too close. Once it feels safe again, it will move away or return to what it was doing. Often, when filming defensive snakes, I've seen them advance towards me only to dart for cover at the first opportunity. This behaviour is simply the snake telling you to back off so it can escape.

Although these advances may seem aggressive, the snake’s intention is not to bite you. Biting is a last resort because physical contact with a predator increases the risk of injury, such as broken fangs or retaliation. A snake only "chases" with the intent to bite and envenomate its prey.

For example, when brown snakes hunt, they actively bite and constrict their prey to secure it, delivering venom without hesitation. Unlike their defensive behaviours with humans, they don’t waste time warning their prey—they strike immediately and decisively. If snakes behaved this way in every encounter with humans, the consequences would be catastrophic, leading to significantly higher rates of envenomations and fatalities.

Image above: Speckled Brown Snake (Pseudonaja guttata) performing offensive advancing, Kynuna, Queensland

Image above: Speckled Brown Snake (Pseudonaja guttata) performing offensive advancing, Kynuna, Queensland

Biting

As a last resort, a snake may bite if previous defensive behaviours haven’t been effective or if there was no time for defensive actions, such as when a snake is stepped on. It’s important to note that many defensive bites are dry bites, where no venom is delivered. Read on to learn more about dry bites.

Above image: Eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textillis) Toowoomaba, Queensland

_________________________________________________________________

What is a Dry Bite and How Do They Occur?

A venomous snake bite occurs when the snake’s fangs pierce the skin, and venom is injected through the fangs via venom ducts. This happens when the snake bites with enough pressure to activate muscles around the venom glands, forcing venom into the target.

A dry bite happens when a venomous snake bites but does not inject venom. This can occur if the snake bites with insufficient pressure, or the fangs make contact without injecting venom. Dry bites are often associated with defensive behaviour, where snakes may mock strike or deliver quick, glancing bites.

It is widely accepted that venomous snakes instinctively know when to use venom and when not to. When they bite prey, they aim to inject venom to subdue it. However, in defensive encounters, snakes may conserve venom for several reasons:

- Energy Conservation: Venom is a valuable resource, and using it on a non-prey target may be wasteful.

- Effectiveness: In some defensive situations, venom may not act quickly enough to deter a threat, especially if the snake is in immediate danger.

For example, the Eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis), responsible for the most human fatalities in Australia, has a 20-40% envenomation rate in human bites, with 60-80% of bites being dry. This suggests that these snakes often conserve venom, using it primarily for capturing prey rather than during defensive encounters.

Although dry bites are less likely to result in envenomation, they can still cause pain, swelling, and infection. Regardless of whether venom is injected, any snake bite should be treated seriously and promptly, as immediate medical attention is essential to avoid complications.

Above image: Eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textillis) Winton, Queensland

Above image: Eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textillis) Winton, Queensland

_________________________________________________________________

What to Do If You Encounter a Defensive Snake

If a snake reacts defensively to you—such as rearing up, flattening its neck, or mock striking—your top priority is to remove yourself from the snake’s vicinity as quickly and calmly as possible. Once you are at a safe distance or out of the snake’s line of sight, it will likely no longer view you as a threat and will return to its natural behaviour.

If you find yourself unexpectedly close to a snake, such as almost stepping on one or having one slither past you, remain absolutely still. Freezing in place is the best way to avoid provoking the snake. Any movement could alert the snake to your presence, triggering a defensive reaction. Allow the snake to move away at its own pace. If the snake remains calm and doesn't feel threatened, you can slowly move away when you feel it is safe to do so.

Above Image: Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) in defensive posture, the Overland Track, Tasmania

_________________________________________________________________

What to Do If You Encounter a Snake

If you spot a snake in the wild, remember that it is part of the natural environment. Keep your distance and observe from afar. Do not approach the snake, as this may provoke a defensive reaction.

If you find a snake in your yard, stay calm. First, move any children or pets indoors and alert others nearby, including neighbours if necessary. If possible, have someone keep an eye on the snake until professional help arrives. This will assist snake catchers in locating the snake and provide peace of mind knowing where it went.

In most cases, snakes are just passing through in search of food, water, or a mate. If the snake stays on your property and you want it removed, contact a local snake catcher. Save their contact details in your phone for quick access, and call them while keeping an eye on the snake.

If the snake is inside your house, try to contain it in one room by closing internal doors and rolling up a towel to block the bottom of the door. Never attempt to remove the snake yourself unless you have the proper training and permits.

_________________________________________________________________

When people recount experiences of being 'chased', many mistakenly believe the snake is trying to catch and bite them. Please see the Offensive Advancing section to better understand this behavior.

_________________________________________________________________

Are Australian snakes territorial?

In Australia, many people mistakenly believe snakes are territorial. Unlike territorial animals like wolves or lions, which mark and defend a specific area, snakes do not claim or protect territories. Instead, snakes have a 'home range'—a defined area where they search for resources such as prey, water, shelter, and mates during the mating season.

The misconception that snakes are territorial often arises from misunderstanding their defensive behaviour. When a snake acts defensively, it’s protecting its personal safety because it perceives you as a threat, not defending a territory.

In the case of male snakes engaged in combat, it's also wrongly assumed they are fighting over territory. In reality, they are fighting for dominance, with the winner gaining the right to mate with a nearby female—not to control more land.

Image above: Tiger snake (Notechis scutatus) Barrington Tops, New South Wales. Tiger Snakes are often labelled as 'territorial' due to their defensive behaviour, but they are actually defending their personal safety, not a specific territory.

Image above: Tiger snake (Notechis scutatus) Barrington Tops, New South Wales. Tiger Snakes are often labelled as 'territorial' due to their defensive behaviour, but they are actually defending their personal safety, not a specific territory.

_________________________________________________________________

Do snakes protect their young or eggs?

In Australia, most snake species do not exhibit parental care. Female snakes typically lay their eggs in secluded locations, such as soil depressions, mammal burrows, or under rocks, leaving them to develop and hatch independently. For example, the bandy-bandy (Vermicella annulata), an Australian elapid, lays its eggs in late summer and does not tend to them afterward. However, exceptions do exist. Notably, Carpet Pythons, an oviparous (egg-laying) species, exhibit maternal care, which is rare among Australian snakes. After laying clutches of 10 to 50 eggs, female Carpet Pythons coil around them, providing protection and regulating temperature through muscular contractions (shivering osmosis). This care continues until the hatchlings emerge, after which the female abandons the nest.

Image above: Coastal Carpet Python (Morelia spilota) coiled around her clutch of eggs.

_________________________________________________________________

If I see a baby snake, will there be a protective parent around?

From day one, hatchling or newborn Australian snakes are equipped with every instinct they need to survive independently from their parents. The father leaves the female immediately after they mate, so there is never a protective father around.

In oviparous (egg-laying) species, the mother leaves the eggs soon after laying them; the exception is Carpet Pythons, as outlined above.

In ovoviviparous species — snakes that give birth to live young in embryonic sacs — the mother typically provides no care after birth. The young disperse and lead solitary lives, just as their parents did. However, there are some exceptions. For example, the red-bellied black snake (Pseudechis porphyriacus) gives birth to live young in late summer or early autumn. While maternal care is minimal, some behaviors suggest limited care; pregnant females may share retreats and bask together in small groups, particularly during late pregnancy. Despite these behaviors, the species does not exhibit strong parental care, and the young are left to fend for themselves once born.

Summary: In most cases, if you encounter a juvenile snake, you won't find a protective parent nearby. The parent typically leaves the young to fend for themselves. The only exceptions are Carpet Pythons, where the mother will stay with her eggs, and occasionally, you may find a mother with her young shortly after birth. However, once the young are born, they quickly become independent, and no protective behavior is shown.

Image Above: Mother and neonate (newborn) Bardicks (Echiopsis curta) Wanneroo, Western Australia. Image credit: Brian Bush. These neonate Bardicks will leave their mother to fend for themselves within hours of being born. As with all Australian venomous snakes, their mother does not provide maternal care post-birth.

_________________________________________________________________

Is a bite from a juvenile venomous snake more dangerous because they can’t control the amount of venom they deliver?

A bite from an adult snake will always have the potential to be more severe than a bite from a juvenile due to the superior physical attributes and abilities of the adult snake.

Juveniles have much smaller fangs, less venom and a lot less experience biting and envenoming prey than their adult counterparts. If a juvenile snake exhausted all of its tiny venom reserves, it may only be a fraction of what an adult could deliver, even if the adult were conserving its venom.

That said, it would be a mistake to underestimate juveniles of highly venomous species; they can possess enough venom to deliver a fatal bite to an adult human. Whether a bite is from a juvenile or adult, treat all snake bites the same, apply snakebite First Aid and seek urgent medical attention.

Image above: Juvenile Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) Yallingup, Western Australia. At no more than 15cm long, their venom still has the potential to kill.

_________________________________________________________________

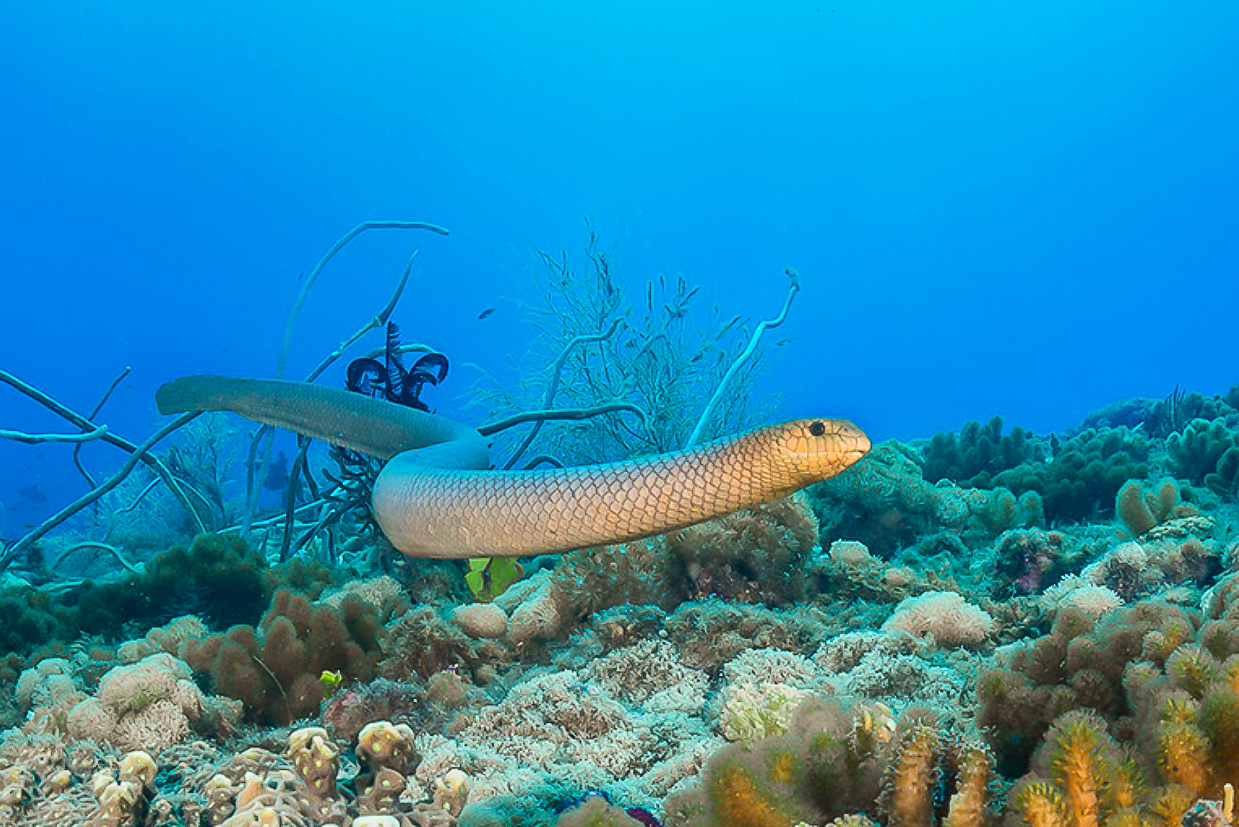

Is it true that Sea Snakes can only bite divers between their fingers because they have small mouths and rear fangs?

No, this is a common misconception. Sea snakes evolved from terrestrial (land-dwelling) venomous snakes (elapids). They have the same fang structure (fixed fangs located at the front of the upper jaw) and highly toxic venom. Essentially, sea snakes can bite and envenom you in the same fashion as any of our terrestrial venomous snakes can.

Like terrestrial venomous snakes, sea snakes have relatively short fangs (2-5mm). Often clothing (or wetsuits) offer protection from a bite; it merely comes down to where you are bitten and if you have enough clothing (or wetsuit material) as protection.

That said, sea snakes are well-known to be curious and inoffensive unless stressed or handled inappropriately. If one approaches you curiously in the water, stay calm and let it observe you or move away if you do not feel comfortable. Never kick or take swipes at the snake to scare it away. Abrupt or aggressive actions such as these may provoke a defensive reaction.

Olive sea snake (Aipysurus laevis) SS Yongala, Queensland. Image by Rafi Amar (https://www.rafiamar.com/)

_________________________________________________________________

Can you identify a non-venomous from its larger head size?

I strongly recommend that head size not be used to determine if a snake is venomous or not. Admittedly, non-venomous pythons generally have larger heads that are distinct from the neck, compared to most Australian venomous snakes with generally smaller heads and minor distinction from the body. That said, there are always exceptions - venomous Death adders, like pythons, have large heads, distinct from the neck. Conversely, non-venomous Australian keelbacks, like venomous brown snakes, have small heads with little distinction. See comparisons below.

Below, both carpet pythons and death adders have large heads that are distinct from the neck/body.

Below, both the non-venomous Australian Keelback and the highly venomous Western Brown Snake have small heads that are not distinct from the neck/ body, further demonstrating that head size is not a good indication of whether a snake is venomous or not.

_________________________________________________________________

Is a King Brown a Brown Snake or a Black Snake

The Common Misconception

The King Brown Snake, aka Mulga Snake (Pseudechis australis) is a black snake, not a brown snake. They are one of eight species of black snakes in the genus Pseudechis and are closely related to the well-renowned Red-bellied black snake (Pseudechis porphyriacus).

The confusion comes from the word 'brown' used in the common name King Brown. In this instance, 'brown' refers to the general colouration of the snake, not the genus, and 'King' relates to its large size and propensity to eat other snakes, similar to the King Cobra.

The Common Name Debate

There has been a long-standing debate over whether this species should be called Mulga Snake or King Brown. These common names both have merit and flaws; read on for more detail.

Those opposed to using King Brown often argue that utilising 'brown' in the common name alludes to this species being part of the brown snake genus (Pseudonaja), which might confuse hospital staff resulting in the wrong antivenom being administered to a bite victim. However, this argument is invalid because hospital staff have protocols and tests that do not rely on bite victims to positively identify the snake.

Apart from the name King Brown irritating snake enthusiasts who grow tired of correcting people that King Browns are actually black snakes, the name King Brown is fairly accurate when referring to the general description of this snake. 'King' relates to its large size and tendency to eat other snakes, similar to the King Cobra, and 'Brown' refers to its typical colour.

The only real flaw with the name King Brown is that King Browns' aren't always brown in colour. Depending on the habitat and the genetics in different populations, their colouration can vary considerably from various shades of brown to creme, dark red, olive-green, golden and almost black.

Now let's look at the common name of Mulga Snake. 'Mulga' refers to a type of tree (Mulga trees) that occur throughout a large portion of this snake's distribution. Still, this species occupies a wide variety of habitats across Australia, not just mulga-dominated habitats. Therefore, calling it a mulga snake is not entirely accurate either.

Humans love a good argument, but if you want to be accurate, refer to this snake by its formal scientific name Pseudechis australis. Pseudechis is the Latin name given to Australian black snakes and translates to 'false Echis' (Echis is a genus of adders). The second part of the name - australis refers to the wide distribution of this species across Australia.

To cover all bases refer to this snake as the Mulga Snake, aka King Brown (Pseudechis australis).

_________________________________________________________________

Snakes are protected wildlife under Australian Law. It is even illegal to touch a snake without a permit in most states. However, you are permitted to use whatever means necessary to protect yourself, your pet or your family member if they are being attacked by a wild animal, including lethal force if necessary.

This use of force is often a grey area for some people, so let me explain the difference. If a snake attacks you, your family member or your pet and you use a garden tool to fight it off, killing the snake in the process, you are not breaking the Law. This DOES NOT include encountering a snake on your property, going and getting a gun or shovel and killing it simply for being a snake. Moreover, It certainly does not include going into the bush and killing snakes in their natural habitat. These acts are illegal, immoral, unsafe and completely unnecessary.

_________________________________________________________________

Am I protecting my family by killing snakes?

In Australia, we only have around two deaths a year attributed to snakebite, so they are nowhere near as dangerous as the public perceives them to be. Statistics indicate that children are rarely bitten, and it's usually adult males trying to kill, capture or otherwise interfere with the snake. If you want to protect your family, you are no good to them if you get bitten.

Furthermore, killing snakes is a 'band aid' solution. It does very little, if anything, to solve the property owners 'perceived snake problem'. The following reasons are why you should not kill snakes.

- Snakes are protected wildlife, and it is illegal to kill them - heavy fines apply.

- By confronting the snake to kill it, you are significantly increasing your chance of being bitten. You are no use to your family in a hospital bed or dead.

- Better the devil you know - Eliminating the resident snake (or snakes) opens up a niche for other snakes to fill. If you remove snakes, vermin numbers increase, and you will likely attract more snakes. New snakes may not know the area as well as the ones that grew up there and may not be as good at keeping out of your way.

- Snakes are nature's best form of pest control. Without snakes, introduced rats and mice can reach plague proportions, spreading disease and impacting farmers' livelihood. Ironically, the majority of farmers kill the very animals helping them.

- Australia is home to around 215 species of snakes, of which about 40 species of terrestrial (land-dwelling) venomous snakes possess venom that is potentially life-threatening to humans. Of those, approximately ten species are recorded to be responsible for human fatalities.

- Snakes are a vital part of the ecosystem. They play an essential role as middle-order predators, meaning they keep other animals' populations balanced. Additionally, snakes are a food source for animals higher in the food chain, such as birds, carnivorous mammals and other reptiles. Snakes, like any other form of wildlife, have a crucial role to play in nature. Killing wildlife because you fear it or simply do not understand it is ignorant and immoral and only serves to unbalance our already fragile ecosystem.

- Most people cannot identify the species they are killing. Often, harmless legless lizards or non-venomous snakes are killed due to the person's lack of knowledge and ignorance. In my teens, I remember my step-father killing a harmless black-headed python on our farm because he thought it was an Inland Taipan, simply because it had a black head. If he had known more about the snakes in his area, he might have known that inland taipans did not occur in our region and that Black-headed pythons are non-venomous and harmless. Furthermore, Black-headed pythons prey on other reptiles, including venomous snakes. The very snake he killed would have eliminated more brown snakes than he ever could have.

Image above: Burton's legless lizard (Lialis burtonis) Exmouth, Western Australia. Australia is home to over 44 species of legless lizards. Despite being non-venomous and harmless, they are often mistaken for snakes and sadly suffer the same fate.

_________________________________________________________________

What action can I take to prevent snakes and to keep my family and pets safe?

First and foremost, killing snakes is the LEAST effective way to protect your family and pets because it is reactive rather than proactive, not to mention dangerous. Killing snakes does little, if anything, to solve one's perceived 'snake problem'. There are far more practical measures you can take, and I will list them below. (Pets I will cover in the next segment called Snakes & Pets).

Precautionary measures

- Learn your local snakes to know which are potentially harmful and which are not. You can purchase books, mobile phone apps or snake identification posters. Alternatively, reach out to your local snake catcher or venomous snake handling training provider and ask them if they can provide or recommend any of this material.

- Save your local snake catcher's number in your phone and call them for advice and relocations.

- Do not attract snakes in the first place. Snakes are often attracted to yards and houses when the human inhabitants unknowingly provide food, water and shelter for the snake. Many of our large mobile venomous snakes eat rodents and become attracted to our homes, yards, farm sheds and chook pens to hunt rats and mice. To reduce mice and rats, use mechanical traps and do not feed them - keep grain and pet food in sealed containers.

- Wear closed in shoes and long pants when bushwalking or working in the yard, and use gloves when gardening. Most of our venomous snakes have short fangs, and clothing can offer protection against a bite.

- Use a torch when walking around at night and stick to main paths or roads rather than cut through the bush or long grass.

- Houses and yards can be an attractive place for snakes to shelter. Carpet pythons and tree snakes enjoy the security and warmth of roofspaces and ceilings, while terrestrial snakes such as brown snakes, taipans, black snakes and others will shelter underneath concrete slabs, in timber and rubbish piles, and under sheets of corrugated iron. Keep materials stacked up off the ground and your yard tidy.

- Snakes prefer not to move around in open areas to avoid being attacked by birds of prey and other predators. Keeping your grass short and gardens maintained will provide snakes with less cover. Avoid low shrubbery up against the house as it provides cover for snakes close to the home.

- Setting a good example around wildlife is extremely important for children. If a child witnesses an adult kill a snake or adults talking of their hatred for snakes, children will be more likely to imitate their parents when they encounter one. The same applies to spreading your fear of snakes. If you are fearful of snakes, do not pass this onto your children. It is essential to teach your children the realistic potential danger of snakes while maintaining a healthy respect for all wildlife, not just the cute stuff.

- Learn snakebite First Aid and have a snakebite First Aid kit easily accessible in your home, vehicle and on your person if you are bushwalking or working in the bush.

- If you regularly have snakes around the house, why not complete a venomous snake-handling course so you can safely remove them. Completing this course will give you the confidence and knowledge to manage the issue yourself. You can locate course providers by searching 'venomous snake handling courses' in Google, followed by your town.

- Complete a Basic First Aid course and keep your certification current. It will teach you snakebite First Aid and many other crucial skills to respond to various emergencies.

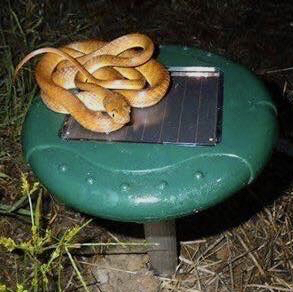

- Snake repellent devices (solar-powered pulse-emitting units) are NOT proven to be effective, and no research supports their effectiveness to repel snakes. In my opinion (and among the wider reptile community), they are a useless product designed to make a quick buck off peoples' fear of snakes. The same applies to any concoctions of chemicals or oils marketed as snake 'deterrents' or 'repellents'.

Image left: Brown tree snake sitting on the warm solar panel on top of a so called "snake repeller".

_________________________________________________________________

Each year in Australia, veterinarians record between 6000-7000 snakebites on domestic animals. For Australian pet owners, the conflict between snakes and domestic pets is a genuine risk. Dogs can be curious or territorial towards snakes, while cats instinctually hunt snakes and other wildlife for fun.

When suddenly greeted by a domestic animal, venomous snakes can become defensive and bite to defend themselves, while non-venomous pythons and tree snakes often target our small furry and feathery pets for an easy meal. With over 215 species of snakes in Australia and half of those venomous, it is not an issue that is going away anytime soon. You can, however, minimise the risk significantly by adopting a proactive attitude and knowing which precautions to take.

Precautionary measures

-

Walk your dog on a lead while in bushland, and do not allow them to wander off into long grass or bushland at beaches, parks or nature reserves.

- Train your pets. The cost of treating a dog for snakebite typically ranges between $4000 - $8000. Avoiding expensive vet bills are an excellent reason to invest in dog training. You can go as far as having your dog specifically trained to avoid snakes (snake avoidance training), or at the very minimum, provide your dog with a level of training so they will come when called. If your dog is wandering off into bushland or investigating something suspicious, simply being able to call it back might avoid a snakebite. Google search for snake avoidance training in your local area.

- Have your vet's current emergency contact details and address saved in your mobile phone.

- Consider obtaining pet insurance to avoid those hefty vet bills.

- Protect your pets. Pythons and Brown tree snakes regularly enter chicken pens, bird aviaries and guinea pig enclosures to prey on the occupants. They also hunt for rodents and possums in roofs and ceilings. Ensure your aviaries and pet enclosures are snake proof with 1x1cm steel mesh and do not forget to secure their enclosures or bring them in before dark.

- Keep cats indoors at all times. Allowing them to roam and kill wildlife is a major problem in Australia. Keeping them indoors keeps your cat safe from snakes, cars and dogs while reducing the chance of injuries due to fights with other cats. If you want your cat to experience outdoor playtime, consider making them an outdoor enclosure or run.

- Supervise puppies and kittens while they are outdoors on any property with nearby bushland. Pythons may sit on verandas and in gardens waiting for an easy meal. Your pets are most at risk between dusk and dawn, as these snakes often hunt at dark.

- Know the signs and symptoms of snakebite. Early detection of snakebite will give your pet the best chance to survive a bite.

Signs & Symptoms may includes:

-

Weakness or severe lethargy

-

Paralysis or collapse

-

Shaking or twitching

-

Dilated pupils

-

Difficulty blinking or opening eyes

-

Vomiting

-

Loss of bladder or bowel control

-

Blood in urine

-

loss of function of body movements/ difficulty walking

-

Breathing difficulties (rapid and shallow)

-

Excessive drooling

-

Bleeding from the bite site

These are only some of the more common symptoms. Your pet can display some, all or other symptoms not listed here. The important thing is that if you suspect a snake has bitten your pet, take them to the vet immediately for a proper assessment.

Image above: Carpet pythons will invade any enclosure they can fit into for an easy meal. In this case they were just after the eggs, however larger pythons may take the chickens.

Image above: Carpet pythons will invade any enclosure they can fit into for an easy meal. In this case they were just after the eggs, however larger pythons may take the chickens.

Image left: Protect your pets with 1x1cm steele mesh enclosures.

Image left: Protect your pets with 1x1cm steele mesh enclosures.

Image right: A dog narrowly escapes death while killing an Eastern Brown snake.

_________________________________________________________________

Australian Snakebite first Aid

If you or someone you are with is bitten by a snake, following the below steps significantly improves your chances of survival.

- Remove yourself (or the patient) from danger

- Call an ambulance/ send for help. If you are alone and have no means to call for help, then apply a pressure bandage as outlined in step 4 and calmly move to where you can reach help.

- Keep the patient as still and calm as possible

Perform the Pressure Immobilisation Technique by:

- Remove any watches or jewellery from the affected limb ASAP. If swelling occurs, these items may restrict blood flow and cause severe discomfort.

- If bitten on a limb and assuming you have the recommended minimum of 2 x bandages, apply the first bandage over the bite site as soon as possible. Elasticised bandages (10-15cm wide) are preferable over standard crepe bandages. If neither are available, clothing or other material should be used.

- Apply the second bandage, commencing at the fingers or toes of the bitten limb and extending upward, covering as much of the limb as possible. WARNING: DO NOT APPLY THE BANDAGE SO TIGHT THAT YOU CUT OFF CIRCULATION. The intention of the bandage is not to stop blood flow. The bandage should moderately compress the skin to trap the venom in the lymph (clear fluid under the skin). The bandage should be firm, and you should be unable to EASILY slide a finger between the bandage and the skin.Alternatively, a single bandage may be used to achieve pressure on the bite site and immobilisation of the limb. In this method, the bandage is initially applied to the fingers or toes and extended up the limb as far as possible to cover both the limb and the bite site.

- Splint and immobilise the limb.

- Keep the patient immobilised and at rest until help arrives.

- If the patient falls unconscious and stops breathing at any stage, CPR must commence immediately. CPR takes priority over the Pressure Immobilisation Technique. If possible, use a second person to complete the Pressure Immobilisation Technique, but do not interrupt CPR to do this.

- Monitor patient's breathing and circulation until help arrives. In some remote areas where ambulance services could be delayed or unable to access your location, consider travelling to meet the ambulance. Caution - keep the patient immobilised and at rest at all times during transport.

DO NOT cut or excise the bitten area or attempt to suck venom from the bite site.

DO NOT wash the bitten area.

DO NOT apply an arterial tourniquet. (Arterial tourniquets that cut off circulation to the limb are dangerous and NOT advised for any type of bite or sting in Australia)

DO NOT bandage individual fingers or toes.

DO NOT remove the bandages or splints before evaluation in an appropriate hospital environment.

References for this above info is the ARC (Australian Resuscitation Council), which is the leading body in Australia for First Aid.

DISCLAIMER - the information I have provided here is GENERAL INFORMATION ONLY and should not substitute formal First Aid training.

_________________________________________________________________

Don’t miss my educational film, where I cover everything every Australian should know about venomous snakes and their behavior. In this short film, you’ll witness fascinating, never-before-seen footage of Australian venomous snakes. I’ll share vital information about these snakes and reveal the truth behind snakebites and animal-related fatalities in Australia. You’ll also get a detailed breakdown of the defensive behaviors of Australian venomous snakes, and I’ll demonstrate the proper way to respond if you encounter one.