Snakes explained: Correcting misinformation about Australian snakes

By Ross McGibbon

About the Author

The information I provide on this page derives from a life-long obsession with snakes, coupled with my experience working with these animals professionally, both as a snake catcher and a wildlife photographer specialising in venomous snakes. I use the content I capture in the field to be an ambassador for reptiles and educate the public about snake safety and awareness via my online platforms (YouTube, Facebook, Instagram & Flickr).

In my spare time, I study reptiles (unofficially) and strive to keep up to date on new research and anything reptile related. The topic of venom and snakebite are of particular interest to me. Furthermore, I am a full-time career firefighter, and I'm passionate about public safety. As a firefighter, I am qualified in advanced First Aid, and I have first-hand experience in snakebite treatment (both as the patient and the one providing the First Aid). I believe at this stage in my life, I have the required knowledge and experience to advise the public on snake safety and awareness.

Image - Photographing A beautiful Black Tiger Snake in the Tasmanian highlands, Australia

_________________________________________________________________

SHORT FILM: DEADLY AUSTRALIAN SNAKES & THEIR BEHAVIOUR

DON’T MISS my educational film covering what every Australian needs to know about Australian venomous snakes and their behaviour. In this short film, you’ll see fascinating and never before seen footage of Australian venomous snakes. I’ll provide you with important information about Australian snakes. I’ll expose the truth about snakebite and animal related deaths in Australia. I’ll give you a detailed breakdown of the defensive behaviour of Australian venomous snakes, and finally, I’ll demonstrate the correct way to respond if you encounter a snake.

_________________________________________________________________

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Australian snakes the deadliest in the world?

When are Australian snakes most active?

Do Australian snakes hibernate or brumate during Winter?

Are snakes more aggressive during mating season?

What is a dry bite and why does this occur?

What to do if a snake reacts defensively to you?

What should do if I encounter a snake?

Are Australian snakes territorial?

Do snakes protect their young or eggs?

If I see a baby snake, will there be a protective parent around?

Can you identify a non-venomous from its larger head size?

Is a King Brown Snake a Black Snake or a Brown Snake?

Am I protecting my family by killing snakes?

What action can I take to prevent snakes and keep my family and pets safe?

Australian Snakebite first Aid

_________________________________________________________________

Are Australian snakes the deadliest in the world?

Australia is home to over 215 species of snakes - more than any other country. Nearly half of these are terrestrial (land-dwelling) venomous snakes. It sounds daunting if you dislike snakes; however, only about 40 of these terrestrial species possess venom that is considered potentially life-threatening to humans. Of these 40 species, roughly 10 are recorded to be responsible for human fatalities.

Many of Australia's highly venomous snakes became infamous when in 1979, they topped the charts (the LD50 test) for having the most potent venom in the world. Many well-known Australian venomous snakes were tested, along with a selection from overseas, resulting in a list of 'the most venomous snakes in the world'. Since these results were published, the information has been subject to gross misinterpretation. The media, the public and snake enthusiasts alike have all put their spin on it to suit their agenda, in many cases wearing it like a badge of honour at the expense of the snake's reputation.

How many times have you heard that Australia has 9 of the top 10 deadliest snakes in the world, or a snake enthusiast boasting that, "This snake is the second most venomous in the world?" If you do your research, you will find that the LD50 test was purely an academic exercise to compare venom toxicity from a sample of snake species using standardised test subjects - mice. The results of which were not intended to gauge how dangerous or deadly these snakes are to humans.

Listed below are some of the major shortfalls with using the 1979 LD50 test results as a basis for ranking snakes as the most venomous, deadly or dangerous in the world:

- The LD50 test uses mice as test subjects, not humans. Therefore, the results do not provide an accurate representation of how harmful that venom is to humans.

- The 1979 LD50 test used ONLY mice for test subjects. Because venom evolves to be most effective on that snake's preferred prey, if the venoms were tested on frogs, birds, lizards or any other prey type, the results would likely favour the snakes that prefer that particular prey. It is no coincidence that rodents are the preferred prey of most top-ranking snakes on the LD50 list.

- The LD50 test does not include all of the world's 600+ venomous snakes. Many were left out. Additionally, many new species have been discovered since 1979, and a considerable amount of taxonomy changes (classification/ naming of species) have occurred since 1979.

- The LD50 test does not consider the venom yield of the snake (how much venom the snake can deliver in a bite). For example, the eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis) is around two and a half times more toxic than the coastal taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus). However, the coastal taipan is capable of injecting twenty to thirty times more venom. Consequently, the result of a taipan envenoming in real life may differ substantially if the coastal taipan injects eight to twelve times more lethal doses than the eastern brown snake.

To summarise, the LD50 test is a valuable exercise for scientists comparing the toxicity of venoms (given that human testing will likely never occur). Still, the results of such experiments should not be used to suggest how dangerous or deadly a species is for humans. Moreover, the terms dangerous, deadly and most venomous do not mean the same thing.

In order to measure how dangerous a particular species of snake might be, several crucial factors must be considered, such as the snake's size, behaviour, temperament, habits, venom yield, fang size, prey type, rates of envenomation on humans, number of human fatalities attributed to that species, the likelihood of contact with humans and how the venom is known to affect humans.

The term deadly refers to how many human fatalities are attributed to that species (usually represented annually). Snakebite causes an annual death toll of between 81000 - 138000 people worldwide. Australia accounts for only two of those on average per year; our snakes are certainly not the deadliest.

In closing, Australia indeed contains more venomous snakes than any other country in the world. We also have the highest number of medically significant snakes (snakes that possess venom that is potentially life-threatening to humans). However, for their venom to become life-threatening, first a bite and successful envenoming must occur, and our snakes do not bite and envenom many people. Australia records around 200-500 snakebite cases annually, and around 100 require antivenom, resulting in an average of only two human fatalities per year. Compare that to 50,000 snakebite deaths recorded in India each year, and you have your answer. Are Australian snakes the deadliest or most dangerous in the world? Not by a long shot.

As a member of the public, avoid getting your information about snakes from questionable sources of mainstream media (newspapers, for example) or other members of the general public via social media. Stick to factual information from reputable sources such as recently published reptile books and literature or your local reptile professional. Learn practical information only, such as which potentially dangerous snakes live in your area, what precautions you can take to minimise the risk of being bitten and what action you need to take if you suspect you have been bitten.

_________________________________________________________________

When are Australian snakes most active?

All aspects of a snake's life rely on their ability to regulate their body temperature, whether it is to hunt prey, digest a meal, find a mate, fight off disease and infection, or even to pump blood around their bodies. Considering reptiles cannot generate their internal body warmth, Their activity levels are subject to the climate. As a result, activity patterns for snakes vary dramatically with the seasons. For most Australian reptiles, activity increases in the warmer months and decreases in the cooler months.

When Spring arrives in September, and the weather begins to warm up, activity levels increase dramatically. The warmer weather triggers most Australian snakes to breed. Female snakes need to hunt more in preparation for developing their eggs/young during mating season, and males travel long distances to find reproductive females. In some species, males compete for mating rights with females by engaging in male to male combat.

All this activity requires considerable energy output and a lot of food, which explains why snakes are far more active in Spring and Summer. During this period, it pays to be prepared for snake encounters and ensure adequate precautions are taken around the home.

Image above: Lowlands Copperheads (Austrelaps superbus) emerging from the vegetation to bask in the sun, Bakers Beach, Tasmania

Image above: Lowlands Copperheads (Austrelaps superbus) emerging from the vegetation to bask in the sun, Bakers Beach, Tasmania

_________________________________________________________________

Do Australian snakes hibernate or brumate during Winter?

To answer this question, I must first give a brief overview of the term Brumation. This term was coined in 1965 by Wilber W. Mayhew, who saw it fit to differentiate that 'cold blooded' reptiles (ectotherms) don't undertake the same physiological process as other animals, such as birds and mammals (heterotherms or endotherms) do when they hibernate. The term grew popular among reptile enthusiasts and it is still the favoured term today. Despite its mainstream use, there are objections to the term's validity and whether there needs to be a separate term for ectotherms at all. The term hibernate does not make any reference to physiological changes or metabolic processes. It simply means - to spend Winter in a dormant or inactive state. Essentially, as a word, brumation means the same thing.

Should you wish to explore this topic further, visit the below link - https://theobligatescientist.blogspot.com/2010/11/do-reptiles-hibernate-or-brumate.html#more

My advice is to use the term brumation when referring to dormancy in reptiles and hibernation for mammals to avoid lengthy debates with reptile enthusiasts.

So, Do Australian snakes hibernate/ brumate during Winter? Yes, most species in cooler climates become dormant or inactive to varying degrees in Winter; however, the duration depends on the species and the climate. Remember, Australia is a massive continent, and the climate in northern Australia can differ significantly from southern regions during Winter.

In northern tropical parts of Australia, where the temperature is extreme in summer, some snakes, such as the Coastal Taipan, prefer to breed over Winter. Male taipans become more active in Winter as they search for females. Moreover, Snakes that live in cooler climates, such as tiger snakes and copperheads, are very cold tolerant, and they can be active in Winter if the temperature permits. Therefore, in some parts of Australia, it is a mistake to believe that you won't encounter snakes during Winter.

Image above: Coastal Taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) Mount Molloy, North Queensland

Image above: Coastal Taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) Mount Molloy, North Queensland

_________________________________________________________________

Are snakes more aggressive during mating season?

During mating season, some snakes species engage in male to male combat to compete for mating rights with a nearby female. Males will "wrestle" one another, in what is sometimes confused with mating behaviour, to determine who is superior. Following a contest, the weaker male retreats, and the victor wins the right to mate with the female.

While this behaviour is somewhat aggressive towards their rival, there is no scientific evidence that male snakes show more aggression towards people during this period. I offer the following information to explain why some people believe snakes are more aggressive in mating season.

Following a dormancy/ inactive period through the cooler months of the year (brumation), snakes' activity level increases dramatically, peaking in spring and summer. Warmer weather triggers snakes to mobilise to search for food and a mate. Males are more commonly encountered during this period, with usually only one thing on their mind - finding females. Mating season prompts male snakes to track females' using scent trails left behind by females. When a male snake unknowingly follows a scent trail into residential areas, the probability of conflicts between snakes, humans, and pets increases.

When a snake suddenly encounters a person or pet in close proximity, a snake may react defensively. This behaviour has nothing to do with snakes being 'more aggressive during mating season,' they simply come into contact with humans and domestic animals more often during this period and will defend their personal safety, just as they would any other time of year. In summary, the increased frequency of encounters leads to more conflict with snakes in mating season, not increased aggression levels among male snakes.

Image above: Highlands Copperhead (Austrelaps ramsayi) Barrington Tops NP, New South Wales (Photographed while gravid - active in breeding season). Highlands Copperheads are such beautiful natured snakes. They generally avoid biting unless stood on or severely harassed.

Image above: Highlands Copperhead (Austrelaps ramsayi) Barrington Tops NP, New South Wales (Photographed while gravid - active in breeding season). Highlands Copperheads are such beautiful natured snakes. They generally avoid biting unless stood on or severely harassed.

_________________________________________________________________

Aggression, by definition, is the act of attacking without provocation (attacking unprovoked), which snakes do not do. A snake will only bite for two reasons - fear or food. Because we are not prey for venomous snakes, that leaves only fear (the snake fears us and feels the need to defend itself).

The behaviour most people perceive as aggression is indeed misinterpreted defensive behaviour or anti-predator strategies (behaviour designed to warn off predators in the wild). Read on to learn about defensive behaviour in detail.

_________________________________________________________________

When a snake suddenly encounters a larger animal, for example, a human or our pets, they generally feel threatened by our size and may respond in one of the following three ways: Fight, Flight or Crypsis.

Crypsis is derived from a Greek word meaning "hiding or concealment". It refers to the animal's ability to conceal itself, especially from a predator, by having a colour, pattern and shape that allows it to blend into the surrounding environment. To achieve crypsis, a snake may remain perfectly still to avoid detection in the presence of a predator or perceived threat.

Flight or fleeing is when a snake retreats to the nearest available cover upon being disturbed. It is the most common response for wild animals, especially snakes because it negates the risk of being injured or killed in a confrontation.

Sometimes, fleeing is as simple as disappearing into nearby vegetation or down a hole. However, if a snake is confronted while moving across open ground, for example, your front lawn, the nearest cover or means of escape can sometimes be behind the person. When the snake flees for this cover, it can give the impression that the snake is B-lining directly for us or 'chasing' us. In reality, the snake is merely trying to reach safety by getting past you first.

Fight is when a snake feels threatened and believes it must stand its ground and act offensively to ward off a perceived threat. To achieve this, a snake may exhibit the following behaviour:

- Rearing up

- Flattening of the neck

- Mouth gaping

- Thrashing around

- Mock strikes, lunging or head butts

- Offensive advances (charging)

- Biting or dry biting

All of these behaviours are anti-predator strategies, otherwise known as defensive behaviours. They are the behaviour most people have trouble interpreting. Each behaviour is explained in detail below.

Rearing – In the animal kingdom, smaller animals generally back down to larger opponents. Because snakes are so close to the ground and relatively small in stature, if they want to ward off a potential predator, they need to look larger than they are. To achieve this, snakes will rear their forebodies up off the ground to appear taller.

Above image: Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) performing rearing, Rocky Gully, Western Australia

Above image: Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) performing rearing, Rocky Gully, Western Australia

Flattening of the neck – By flattening its neck, a snake can appear larger than it is. We have all seen how well cobras perform this behaviour, but some Australian snakes, such as tiger snakes, red-bellied black snakes and mulga snakes, perform this behaviour quite well. Neck flattening can be performed in addition to rearing or horizontal to the ground, better known as a side-angle defensive display.

Mouth gaping – communicates when a snake is feeling agitated, and it can be as subtle as dropping the lower jaw just a little. Should a snake require maximum intimidation, a full-mouth gape displaying the fangs and mouth lining is employed. Both Taipans and Brown snakes are well known for this behaviour. Above Image: Inland Taipan aka Fierce Snake (Oxyuranus microlepidotus) performing mouth gape, Goyder lagoon, South Australia

Above Image: Inland Taipan aka Fierce Snake (Oxyuranus microlepidotus) performing mouth gape, Goyder lagoon, South Australia

Thrashing – can be used to confuse an opponent or make it difficult for a predator to seize a fast-moving target. Thrashing may also kick up leaf litter and dust to further confuse the predator.

Mock strikes, lunges and head butts – Mock strikes and lunges are the snake's equivalent of a boxer throwing a feint (pretend punch) that intentionally misses or falls short of the target to put their opponent on the back-foot. Snakes do this to give the impression they are striking but without carrying the risk of personal injury by physically coming into contact with their opponent.

A snake may also head-butt to avoid breaking fangs; if a snake was to bite something unnecessarily and damage its fangs, it might not be able to feed for some time until they regenerate.

Offensive advancing – When people tell of being chased by a snake, they generally lack an understanding of the snake's behaviour and intentions. When someone encounters a defensive snake, most people interpret any advance towards them as though the snake is chasing them with intent to catch, bite and inject them with venom; however, this is not the case.

A more accurate explanation of the snake's behaviour in this situation is Offensive advancing; This is when a snake charges towards a perceived predator to force its opponent to retreat. When someone says a snake chased them, this is what they are referring to. It is crucial to understand that this behaviour intends to warn off predators by appearing intimidating.

We've all seen an elephant charge towards another animal that gets too close. When the intruder backs off, the elephant returns to the herd. Like the elephant, snakes perform similar behaviour and may charge at you if you are too close. When you are far enough away for the snake to feel safe again, it will move off or go back to what it was doing.

Countless times while filming defensive snakes, they will advance towards me, only to dart down a hole or into the nearest cover at the first available opportunity. When you see a snake exhibit this behaviour, it is merely telling you to back off so it can escape, or at the very least, feel safe again.

While these advances appear aggressive, it is generally not the snake's intention to catch and bite you because physical contact with an opponent increases the risk of personal injury to the snake, i.e. breaking fangs or retaliation from the animal they are biting. As such, biting is generally a last resort for a snake when defending themselves.

The only thing a snake chases with intent to bite and envenomate is its prey. To demonstrate this, take a look at these brown snakes at feeding time. You'll notice three main differences in how they attack their prey compared to how they defend themselves. When they attack their prey, they wrap around it and use constriction to secure the prey item. They bite and hold on to ensure venom is delivered, and they don't give any warnings in the form of defensive behaviour as they would with us; they just attack their target to the full extent of their ability. If snakes did this each time they encountered a human, we would not stand a chance.

Image above: Speckled Brown Snake (Pseudonaja guttata) performing offensive advancing, Kynuna, Queensland

Image above: Speckled Brown Snake (Pseudonaja guttata) performing offensive advancing, Kynuna, Queensland

Biting - As a last resort, a snake may bite if the former defensive behaviour has not been effective, or there was no time to perform defensive behaviour; for example, the snake is stood on. Furthermore, when a snake bites to defend itself, many defensive bites are dry bites. Read on to learn more about dry bites.

Above image: Eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textillis) Toowoomaba, Queensland

_________________________________________________________________

What is a dry bite and does this occur?

When a front-fanged venomous snake bites down with enough pressure, the muscles around the venom gland contract, forcing venom to flow along the venom ducts and through the fangs. A successful venomous bite generally depends on how effectively the snake has bitten the subject and whether it bites down hard enough to engage the muscles around the venom gland.

When defending themselves against a predator, snakes often mock strike to intimidate their opponent without intending to deliver venom. A dry bite occurs when a snake bites a subject and does not inject venom. Dry bites may be quick glancing bites, where the fangs contact the victim's skin, but the snake does not hold on long enough or bite down with enough force to result in the successful delivery of venom.

While further research on this topic is required, it is becoming widely accepted that venomous snakes inherently know when to use their venom and when not to. Put plainly, when venomous snakes bite prey, they aim to inject venom 100% of the time, or they risk going hungry. Conversely, when venomous snakes bite to defend themselves, they don't always inject venom, presumably for two reasons;

1) There is no situation where the snake benefits from using its venom on a non-prey item; it wastes venom and risks injury to the snake.

2) If a snake faces a life and death situation and a confrontation were to take place. No matter how potent the snake's venom, it will not act fast enough to prevent the predator from killing the snake first, rendering venom worthless as a defensive strategy when delivered from a bite.

In the case of the Eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textillis), the species responsible for the most human fatalities in Australia, statistics reveal that the rate of envenoming on humans is approximately 20-40%, equating to dry bites in 60-80% of bite cases. With such a low rate of envenoming on humans, it stands to reason that they intuitively know not to use their venom on anything they cannot eat.

Above image: Eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textillis) Winton, Queensland

Above image: Eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textillis) Winton, Queensland

_________________________________________________________________

What to do if a snake reacts defensively towards me?

Suppose a snake reacts defensively to you, for example, rearing up, flattening its neck, mock striking etc. In that case, removing yourself from the snake's vicinity as quickly as possible is your highest priority. When you are at a safe distance or out of the snake's view, the snake will no longer perceive you as a threat and will return to its natural behaviour.

If you find yourself suddenly quite close to a snake and you are within striking range, for example, you almost step on one, or one slithers past very close to you, then freezing and remaining extremely still is the best course of action to avoid provoking a defensive reaction from the snake. If you move, you may alert the snake to your presence and cause a defensive response. Allow the snake to move off in its own time, or as long as the snake remains calm, you can slowly move away when you feel it is safe to do so.

Above Image: Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) in defensive posture, the Overland Track, Tasmania

_________________________________________________________________

What should I do if I encounter a snake?

If you see a snake in the wild, remember that they are native wildlife and belong there. Keep your distance and admire from afar. Do not approach the snake as you may provoke a defensive reaction.

If you find a snake in your yard, there is no need to panic. Think safety first and calmly move any children or pets inside and alert anyone in the immediate vicinity and, if necessary, your neighbours. If you can achieve this while someone keeps an eye on the snake, it will help snake catchers locate the snake when they arrive, or it will at least offer you some peace of mind if you know where it went.

If this is the first time you have encountered it, more often than not, the snake is just passing through in search of food, water, or a mate. If it stays on your property and you want it removed, then call your local snake catcher. In this case, being prepared will help towards a successful outcome. Have your local snake catchers number saved in your mobile phone and call them from it while keeping an eye on the snake until he or she arrives.

If the snake is in your house, try to contain the snake to the room it is in by closing internal doors and rolling up a towel and placing it along the bottom of the door. Never try and remove a snake without the appropriate permit, training and experience.

Image above: Dugite (Pseudonaja affinis) Perth, Western Australia. Dugites are the most common snake removed from Perth residents, accounting for up to 80% of relocations. Despite bing highly venomous and very common, there has been only 2 recorded human fatalities attributed to this species in the last 35 years, due to their shy nature. When encountered they prefer to flee and only defend themselves if their personal space is violated.

Image above: Dugite (Pseudonaja affinis) Perth, Western Australia. Dugites are the most common snake removed from Perth residents, accounting for up to 80% of relocations. Despite bing highly venomous and very common, there has been only 2 recorded human fatalities attributed to this species in the last 35 years, due to their shy nature. When encountered they prefer to flee and only defend themselves if their personal space is violated.

_________________________________________________________________

When people recount experiences of being 'chased', most people wrongfully believe the snake intends to catch and bite them. Please see the Offensive Advancing section to better understand this behavior.

_________________________________________________________________

Are Australian snakes territorial?

In Australia, many people wrongly believe that snakes are territorial. Territorial animals such as wolves and lions mark out a piece of land as their territory and defend that area by attacking other territorial animals that trespass. Snakes do not mark out a territory and protect it against humans or our domestic animals. For this reason, it is incorrect to describe snakes as territorial in this manner.

Rather than a territory, snakes have a 'home range' or an area in which they live. They move around within this home range, searching for resources such as prey, water, areas of refuge and a mate during mating season.

I believe snakes are often labelled 'territorial' by those who don't understand what a defensive snake is trying to communicate. These people need to learn that the snake is not defending a territory; it is merely protecting its personal safety because it perceives you as a potential predator or threat to its life.

When male snakes are observed in combat, they are often regarded as territorial; however, they are not fighting to defend their territory; they fight for dominance over their opponent. The victor does not win a larger territory but rather the right to mate with a nearby female.

Image above: Tiger snake (Notechis scutatus) Barrington Tops, New South Wales. Tiger Snakes are often branded as 'Territorial' due to their defensive behaviour, however they are defending their personal safety, not a territory.

Image above: Tiger snake (Notechis scutatus) Barrington Tops, New South Wales. Tiger Snakes are often branded as 'Territorial' due to their defensive behaviour, however they are defending their personal safety, not a territory.

_________________________________________________________________

Do snakes protect their young/ eggs?

The only Australian snakes known to exhibit maternal care are Carpet Pythons. They coil around the clutch of eggs to incubate them until they hatch. When the eggs hatch, the mother is no longer required, and she leaves the hatchlings to fend for themselves. During incubation, if a female Capet Python is coiled around her eggs and harassed, she may strike at the aggressor to protect them; this is the only situation where an Australian snake will defend her offspring.

Image above: Coastal Carpet Python (Morelia spilota) coiled around her clutch of eggs.

_________________________________________________________________

If I see a baby snake, will there be a protective parent around?

From day one, hatchling or newborn Australian snakes are equipped with every instinct they need to survive independently from their parents. The father leaves the female immediately after they mate, so there is never a protective father around.

In oviparous (egg-laying) species, the mother leaves the eggs soon after laying them; the exception is carpet pythons as outlined in the previous section – Do snakes protect their young or eggs?.

In ovoviviparous species - snakes that give birth to 'live young' in embryonic sacks, the mother leaves her young soon after giving birth. The young eventually scatter and go on to live solitary lives, as did their parents.

To summarise, if you see a juvenile snake, there will never be a protective parent around unless you find a carpet python coiled around her eggs.

Image above: Mother and neonate (newborn) Bardicks (Echiopsis curta) Wanneroo, Western Australia. Image credit: Brian Bush. These neonate Bardicks will leave their mother to fend for themselves within hours of being born. As with all Australian venomous snakes, their mother does not provide maternal care post birth.

_________________________________________________________________

Is a bite from a juvenile venomous snake more dangerous because they can’t control the amount of venom they deliver?

A bite from an adult snake will always have the potential to be more severe than a bite from a juvenile due to the superior physical attributes and abilities of the adult snake.

Juveniles have much smaller fangs, less venom and a lot less experience biting and envenoming prey than their adult counterparts. If a juvenile snake exhausted all of its tiny venom reserves, it may only be a fraction of what an adult could deliver, even if the adult were conserving its venom.

That said, it would be a mistake to underestimate juveniles of highly venomous species; they can possess enough venom to deliver a fatal bite to an adult human. Whether a bite is from a juvenile or adult, treat all snake bites the same, apply snakebite First Aid and seek urgent medical attention.

Image above: Juvenile Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) Yallingup, Western Australia. At no more than 15cm long, their venom still has the potential to kill.

_________________________________________________________________

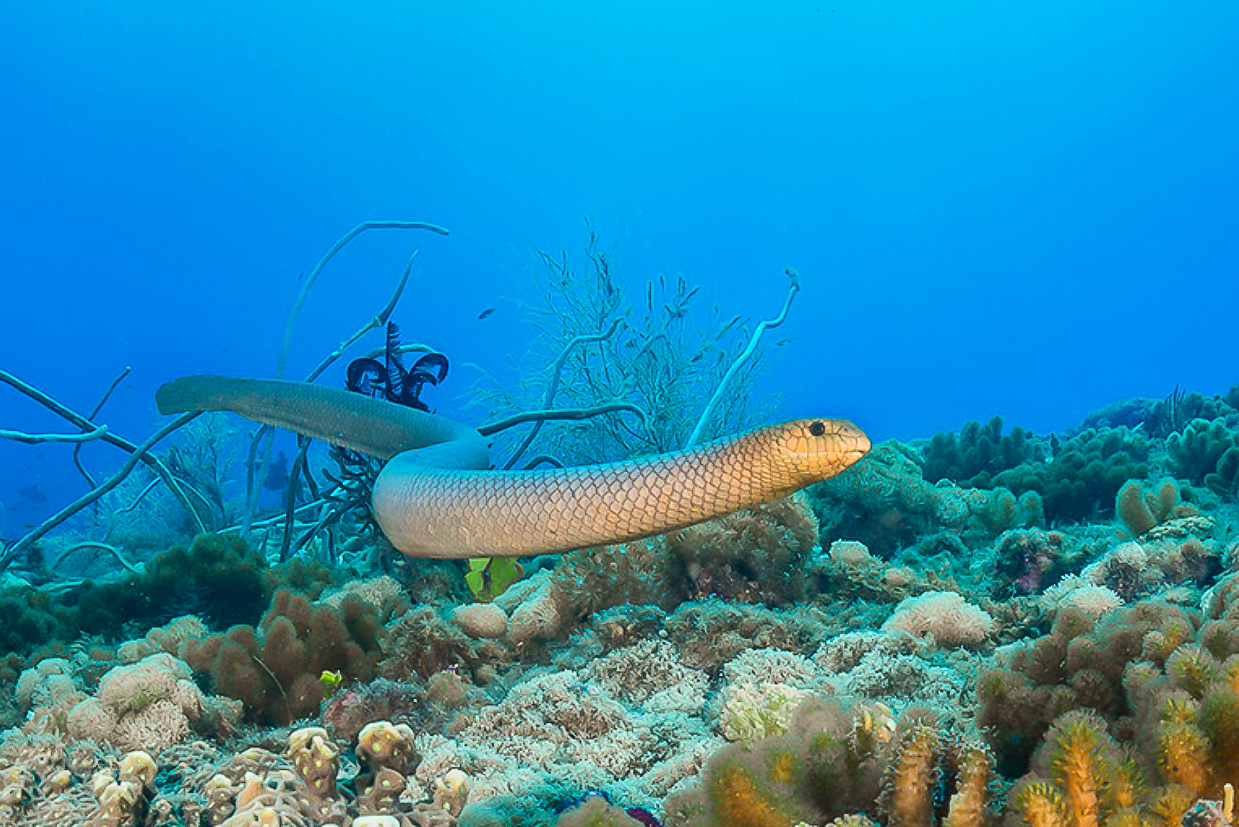

Is it true that Sea Snakes can only bite divers between their fingers because they have small mouths and rear fangs?

No, this is a common misconception. Sea snakes evolved from terrestrial (land-dwelling) venomous snakes (elapids). They have the same fang structure (fixed fangs located at the front of the upper jaw) and highly toxic venom. Essentially, sea snakes can bite and envenom you in the same fashion as any of our terrestrial venomous snakes can.

Like terrestrial venomous snakes, sea snakes have relatively short fangs (2-5mm). Often clothing (or wetsuits) offer protection from a bite; it merely comes down to where you are bitten and if you have enough clothing (or wetsuit material) as protection.

That said, sea snakes are well-known to be curious and inoffensive unless stressed or handled inappropriately. If one approaches you curiously in the water, stay calm and let it observe you or move away if you do not feel comfortable. Never kick or take swipes at the snake to scare it away. Abrupt or aggressive actions such as these may provoke a defensive reaction.

Olive sea snake (Aipysurus laevis) SS Yongala, Queensland. Image by Rafi Amar (https://www.rafiamar.com/)

_________________________________________________________________

Can you identify a non-venomous from its larger head size?

I strongly recommend that head size not be used to determine if a snake is venomous or not. Admittedly, non-venomous pythons generally have larger heads that are distinct from the neck, compared to most Australian venomous snakes with generally smaller heads and minor distinction from the body. That said, there are always exceptions - venomous Death adders, like pythons, have large heads, distinct from the neck. Conversely, non-venomous Australian keelbacks, like venomous brown snakes, have small heads with little distinction. See comparisons below.

Below, both carpet pythons and death adders have large heads that are distinct from the neck/body.

Below, both the non-venomous Australian Keelback and the highly venomous Western Brown Snake have small heads that are not distinct from the neck/ body, further demonstrating that head size is not a good indication of whether a snake is venomous or not.

_________________________________________________________________

Is a King Brown a Brown Snake or a Black Snake

The Common Misconception

The King Brown Snake, aka Mulga Snake (Pseudechis australis) is a black snake, not a brown snake. They are one of eight species of black snakes in the genus Pseudechis and are closely related to the well-renowned Red-bellied black snake (Pseudechis porphyriacus).

The confusion comes from the word 'brown' used in the common name King Brown. In this instance, 'brown' refers to the general colouration of the snake, not the genus, and 'King' relates to its large size and propensity to eat other snakes, similar to the King Cobra.

The Common Name Debate

There has been a long-standing debate over whether this species should be called Mulga Snake or King Brown. These common names both have merit and flaws; read on for more detail.

Those opposed to using King Brown often argue that utilising 'brown' in the common name alludes to this species being part of the brown snake genus (Pseudonaja), which might confuse hospital staff resulting in the wrong antivenom being administered to a bite victim. However, this argument is invalid because hospital staff have protocols and tests that do not rely on bite victims to positively identify the snake.

Apart from the name King Brown irritating snake enthusiasts who grow tired of correcting people that King Browns are actually black snakes, the name King Brown is fairly accurate when referring to the general description of this snake. 'King' relates to its large size and tendency to eat other snakes, similar to the King Cobra, and 'Brown' refers to its typical colour.

The only real flaw with the name King Brown is that King Browns' aren't always brown in colour. Depending on the habitat and the genetics in different populations, their colouration can vary considerably from various shades of brown to creme, dark red, olive-green, golden and almost black.

Now let's look at the common name of Mulga Snake. 'Mulga' refers to a type of tree (Mulga trees) that occur throughout a large portion of this snake's distribution. Still, this species occupies a wide variety of habitats across Australia, not just mulga-dominated habitats. Therefore, calling it a mulga snake is not entirely accurate either.

Humans love a good argument, but if you want to be accurate, refer to this snake by its formal scientific name Pseudechis australis. Pseudechis is the Latin name given to Australian black snakes and translates to 'false Echis' (Echis is a genus of adders). The second part of the name - australis refers to the wide distribution of this species across Australia.

To cover all bases refer to this snake as the Mulga Snake, aka King Brown (Pseudechis australis).

_________________________________________________________________

Snakes are protected wildlife under Australian Law. It is even illegal to touch a snake without a permit in most states. However, you are permitted to use whatever means necessary to protect yourself, your pet or your family member if they are being attacked by a wild animal, including lethal force if necessary.

This use of force is often a grey area for some people, so let me explain the difference. If a snake attacks you, your family member or your pet and you use a garden tool to fight it off, killing the snake in the process, you are not breaking the Law. This DOES NOT include encountering a snake on your property, going and getting a gun or shovel and killing it simply for being a snake. Moreover, It certainly does not include going into the bush and killing snakes in their natural habitat. These acts are illegal, immoral, unsafe and completely unnecessary.

_________________________________________________________________

Am I protecting my family by killing snakes?

In Australia, we only have around two deaths a year attributed to snakebite, so they are nowhere near as dangerous as the public perceives them to be. Statistics indicate that children are rarely bitten, and it's usually adult males trying to kill, capture or otherwise interfere with the snake. If you want to protect your family, you are no good to them if you get bitten.

Furthermore, killing snakes is a 'band aid' solution. It does very little, if anything, to solve the property owners 'perceived snake problem'. The following reasons are why you should not kill snakes.

- Snakes are protected wildlife, and it is illegal to kill them - heavy fines apply.

- By confronting the snake to kill it, you are significantly increasing your chance of being bitten. You are no use to your family in a hospital bed or dead.

- Better the devil you know - Eliminating the resident snake (or snakes) opens up a niche for other snakes to fill. If you remove snakes, vermin numbers increase, and you will likely attract more snakes. New snakes may not know the area as well as the ones that grew up there and may not be as good at keeping out of your way.

- Snakes are nature's best form of pest control. Without snakes, introduced rats and mice can reach plague proportions, spreading disease and impacting farmers' livelihood. Ironically, the majority of farmers kill the very animals helping them.

- Australia is home to around 215 species of snakes, of which about 40 species of terrestrial (land-dwelling) venomous snakes possess venom that is potentially life-threatening to humans. Of those, approximately ten species are recorded to be responsible for human fatalities.

- Snakes are a vital part of the ecosystem. They play an essential role as middle-order predators, meaning they keep other animals' populations balanced. Additionally, snakes are a food source for animals higher in the food chain, such as birds, carnivorous mammals and other reptiles. Snakes, like any other form of wildlife, have a crucial role to play in nature. Killing wildlife because you fear it or simply do not understand it is ignorant and immoral and only serves to unbalance our already fragile ecosystem.

- Most people cannot identify the species they are killing. Often, harmless legless lizards or non-venomous snakes are killed due to the person's lack of knowledge and ignorance. In my teens, I remember my step-father killing a harmless black-headed python on our farm because he thought it was an Inland Taipan, simply because it had a black head. If he had known more about the snakes in his area, he might have known that inland taipans did not occur in our region and that Black-headed pythons are non-venomous and harmless. Furthermore, Black-headed pythons prey on other reptiles, including venomous snakes. The very snake he killed would have eliminated more brown snakes than he ever could have.

Image above: Burton's legless lizard (Lialis burtonis) Exmouth, Western Australia. Australia is home to over 44 species of legless lizards. Despite being non-venomous and harmless, they are often mistaken for snakes and sadly suffer the same fate.

_________________________________________________________________

What action can I take to prevent snakes and to keep my family and pets safe?

First and foremost, killing snakes is the LEAST effective way to protect your family and pets because it is reactive rather than proactive, not to mention dangerous. Killing snakes does little, if anything, to solve one's perceived 'snake problem'. There are far more practical measures you can take, and I will list them below. (Pets I will cover in the next segment called Snakes & Pets).

Precautionary measures

- Learn your local snakes to know which are potentially harmful and which are not. You can purchase books, mobile phone apps or snake identification posters. Alternatively, reach out to your local snake catcher or venomous snake handling training provider and ask them if they can provide or recommend any of this material.

- Save your local snake catcher's number in your phone and call them for advice and relocations.

- Do not attract snakes in the first place. Snakes are often attracted to yards and houses when the human inhabitants unknowingly provide food, water and shelter for the snake. Many of our large mobile venomous snakes eat rodents and become attracted to our homes, yards, farm sheds and chook pens to hunt rats and mice. To reduce mice and rats, use mechanical traps and do not feed them - keep grain and pet food in sealed containers.

- Wear closed in shoes and long pants when bushwalking or working in the yard, and use gloves when gardening. Most of our venomous snakes have short fangs, and clothing can offer protection against a bite.

- Use a torch when walking around at night and stick to main paths or roads rather than cut through the bush or long grass.

- Houses and yards can be an attractive place for snakes to shelter. Carpet pythons and tree snakes enjoy the security and warmth of roofspaces and ceilings, while terrestrial snakes such as brown snakes, taipans, black snakes and others will shelter underneath concrete slabs, in timber and rubbish piles, and under sheets of corrugated iron. Keep materials stacked up off the ground and your yard tidy.

- Snakes prefer not to move around in open areas to avoid being attacked by birds of prey and other predators. Keeping your grass short and gardens maintained will provide snakes with less cover. Avoid low shrubbery up against the house as it provides cover for snakes close to the home.

- Setting a good example around wildlife is extremely important for children. If a child witnesses an adult kill a snake or adults talking of their hatred for snakes, children will be more likely to imitate their parents when they encounter one. The same applies to spreading your fear of snakes. If you are fearful of snakes, do not pass this onto your children. It is essential to teach your children the realistic potential danger of snakes while maintaining a healthy respect for all wildlife, not just the cute stuff.

- Learn snakebite First Aid and have a snakebite First Aid kit easily accessible in your home, vehicle and on your person if you are bushwalking or working in the bush.

- If you regularly have snakes around the house, why not complete a venomous snake-handling course so you can safely remove them. Completing this course will give you the confidence and knowledge to manage the issue yourself. You can locate course providers by searching 'venomous snake handling courses' in Google, followed by your town.

- Complete a Basic First Aid course and keep your certification current. It will teach you snakebite First Aid and many other crucial skills to respond to various emergencies.

- Snake repellent devices (solar-powered pulse-emitting units) are NOT proven to be effective, and no research supports their effectiveness to repel snakes. In my opinion (and among the wider reptile community), they are a useless product designed to make a quick buck off peoples' fear of snakes. The same applies to any concoctions of chemicals or oils marketed as snake 'deterrents' or 'repellents'.

Image left: Brown tree snake sitting on the warm solar panel on top of a so called "snake repeller".

_________________________________________________________________

Each year in Australia, veterinarians record between 6000-7000 snakebites on domestic animals. For Australian pet owners, the conflict between snakes and domestic pets is a genuine risk. Dogs can be curious or territorial towards snakes, while cats instinctually hunt snakes and other wildlife for fun.

When suddenly greeted by a domestic animal, venomous snakes can become defensive and bite to defend themselves, while non-venomous pythons and tree snakes often target our small furry and feathery pets for an easy meal. With over 215 species of snakes in Australia and half of those venomous, it is not an issue that is going away anytime soon. You can, however, minimise the risk significantly by adopting a proactive attitude and knowing which precautions to take.

Precautionary measures

-

Walk your dog on a lead while in bushland, and do not allow them to wander off into long grass or bushland at beaches, parks or nature reserves.

- Train your pets. The cost of treating a dog for snakebite typically ranges between $4000 - $8000. Avoiding expensive vet bills are an excellent reason to invest in dog training. You can go as far as having your dog specifically trained to avoid snakes (snake avoidance training), or at the very minimum, provide your dog with a level of training so they will come when called. If your dog is wandering off into bushland or investigating something suspicious, simply being able to call it back might avoid a snakebite. Google search for snake avoidance training in your local area.

- Have your vet's current emergency contact details and address saved in your mobile phone.

- Consider obtaining pet insurance to avoid those hefty vet bills.

- Protect your pets. Pythons and Brown tree snakes regularly enter chicken pens, bird aviaries and guinea pig enclosures to prey on the occupants. They also hunt for rodents and possums in roofs and ceilings. Ensure your aviaries and pet enclosures are snake proof with 1x1cm steel mesh and do not forget to secure their enclosures or bring them in before dark.

- Keep cats indoors at all times. Allowing them to roam and kill wildlife is a major problem in Australia. Keeping them indoors keeps your cat safe from snakes, cars and dogs while reducing the chance of injuries due to fights with other cats. If you want your cat to experience outdoor playtime, consider making them an outdoor enclosure or run.

- Supervise puppies and kittens while they are outdoors on any property with nearby bushland. Pythons may sit on verandas and in gardens waiting for an easy meal. Your pets are most at risk between dusk and dawn, as these snakes often hunt at dark.

- Know the signs and symptoms of snakebite. Early detection of snakebite will give your pet the best chance to survive a bite.

Signs & Symptoms may includes:

-

Weakness or severe lethargy

-

Paralysis or collapse

-

Shaking or twitching

-

Dilated pupils

-

Difficulty blinking or opening eyes

-

Vomiting

-

Loss of bladder or bowel control

-

Blood in urine

-

loss of function of body movements/ difficulty walking

-

Breathing difficulties (rapid and shallow)

-

Excessive drooling

-

Bleeding from the bite site

These are only some of the more common symptoms. Your pet can display some, all or other symptoms not listed here. The important thing is that if you suspect a snake has bitten your pet, take them to the vet immediately for a proper assessment.

Image above: Carpet pythons will invade any enclosure they can fit into for an easy meal. In this case they were just after the eggs, however larger pythons may take the chickens.

Image above: Carpet pythons will invade any enclosure they can fit into for an easy meal. In this case they were just after the eggs, however larger pythons may take the chickens.

Image left: Protect your pets with 1x1cm steele mesh enclosures.

Image left: Protect your pets with 1x1cm steele mesh enclosures.

Image right: A dog narrowly escapes death while killing an Eastern Brown snake.

_________________________________________________________________

Australian Snakebite first Aid

If you or someone you are with is bitten by a snake, following the below steps significantly improves your chances of survival.

- Remove yourself (or the patient) from danger

- Call an ambulance/ send for help. If you are alone and have no means to call for help, then apply a pressure bandage as outlined in step 4 and calmly move to where you can reach help.

- Keep the patient as still and calm as possible

Perform the Pressure Immobilisation Technique by:

- Remove any watches or jewellery from the affected limb ASAP. If swelling occurs, these items may restrict blood flow and cause severe discomfort.

- If bitten on a limb and assuming you have the recommended minimum of 2 x bandages, apply the first bandage over the bite site as soon as possible. Elasticised bandages (10-15cm wide) are preferable over standard crepe bandages. If neither are available, clothing or other material should be used.

- Apply the second bandage, commencing at the fingers or toes of the bitten limb and extending upward, covering as much of the limb as possible. WARNING: DO NOT APPLY THE BANDAGE SO TIGHT THAT YOU CUT OFF CIRCULATION. The intention of the bandage is not to stop blood flow. The bandage should moderately compress the skin to trap the venom in the lymph (clear fluid under the skin). The bandage should be firm, and you should be unable to EASILY slide a finger between the bandage and the skin.Alternatively, a single bandage may be used to achieve pressure on the bite site and immobilisation of the limb. In this method, the bandage is initially applied to the fingers or toes and extended up the limb as far as possible to cover both the limb and the bite site.

- Splint and immobilise the limb.

- Keep the patient immobilised and at rest until help arrives.

- If the patient falls unconscious and stops breathing at any stage, CPR must commence immediately. CPR takes priority over the Pressure Immobilisation Technique. If possible, use a second person to complete the Pressure Immobilisation Technique, but do not interrupt CPR to do this.

- Monitor patient's breathing and circulation until help arrives. In some remote areas where ambulance services could be delayed or unable to access your location, consider travelling to meet the ambulance. Caution - keep the patient immobilised and at rest at all times during transport.

DO NOT cut or excise the bitten area or attempt to suck venom from the bite site.

DO NOT wash the bitten area.

DO NOT apply an arterial tourniquet. (Arterial tourniquets that cut off circulation to the limb are dangerous and NOT advised for any type of bite or sting in Australia)

DO NOT bandage individual fingers or toes.

DO NOT remove the bandages or splints before evaluation in an appropriate hospital environment.

References for this above info is the ARC (Australian Resuscitation Council), which is the leading body in Australia for First Aid.

DISCLAIMER - the information I have provided here is GENERAL INFORMATION ONLY and should not substitute formal First Aid training.

_________________________________________________________________